Breaking The Monolith II

Transactional Guarantees

Transactional guarantees are one of the hardest challenges when breaking a monolith. They’re the key reason I’d recommend staying in a monolith as long as it is practicable.

We’ve decided to extract our webhook sending component into its own service. This component will be responsible for:

- Storing the webhook configurations for each customer (i.e. whether they receive webhooks, and to what endpoint)

- Receiving events from the core system, grouping them into webhooks, and sending them

- Storing the webhooks that we’ve sent so that customers can view them in the UI to help debug, and resend webhooks that they failed to process

When we build a monolith on a big relational database, we take transactional guarantees for granted. We can view them as a kind of guard rail; developers use them so that they can avoid thinking about failure modes within a particular bit of logic. Breaking the monolith will require us to relinquish some of these guarantees.

Spot the Transaction

If we don’t know where the transactions are, it’s hard to reason about what to do with them. Depending on the structure of our code, and how isolated the component already is, this may be quite a challenge. In this case, it might be a good candidate for isolating the component within the monolith first before trying to extract it.

Some transactional guarantees are there for convenience, but can be easily relinquished if needed. For example, we currently have a single endpoint which allows a customer to update their system configuration. This includes things like their colour scheme and logo, but also includes their webhook endpoint URL and secrets. Currently, the update call to change their colour scheme is wrapped in the same transaction as the webhook endpoint configuration. Maintaining this behaviour would be expensive (as we will see below), so instead we’ve decided to relinquish the guarantees here all together by splitting the API into two separate endpoints (one to update colour and logo, another to update the webhook configuration).

It’s helpful for us to make these changes up front so that we can confirm the behaviour and find any rough edges before we start worrying about multiple services. The more ruthless we can be with these transactions, the easier our journey to multiple services will become. We must think critically about the guarantees we currently provide to internal and external stakeholders, and robustly question how valuable they are. Any guarantees we want to keep will incur significant costs, so they had better be value for money.

Two Phase Commit (2pc)

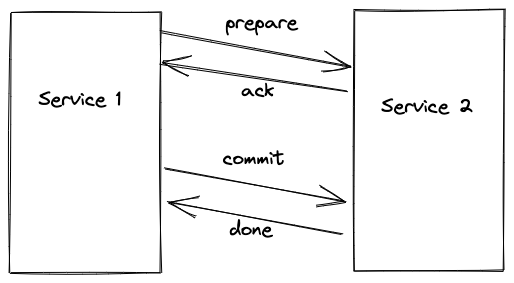

Two Phase Commit is a common strategy employed by many databases to give transactional guarantees across multiple servers. This is what’s happening under the hood with all those clever multi-node databases. It uses a ‘prepare’ phase (which passes all the data and validates it) and a ‘commit’ or ‘rollback’ phase, giving the ‘all or nothing’ atomicity we expect from a database. It’s very robust, but is comparatively slow and relies on lots of synchronous communication.

Depending on how we use 2pc, we run the risk of undermining some of the benefits we are hoping to get from breaking the monolith.

We want to use this so that we are really sure that every time a new employee is created, we send a webhook to the customer. We want to keep our transactional guarantee here because if we don’t send the webhook, it’s possible that someone won’t get added to the payroll which would be a really bad outcome for our customer.

A simple implementation of our use case might look something like:

- Open transaction with the main HR-World database

- Create the new employee in the HR-World database table

employees - Send a

preparemessage to the webhook service with anemployee_createdevent, and wait forack - Commit change in the HR-World database

- Send

commitmessage to webhook service to make sure the webhook gets sent (and really really hope that this doesn’t fail)

The first problem that jumps out is what happens if step 4 or step 5 fails. To give us confidence in this process, we must either:

- Be comfortable with one commit succeeding and the other failing, at least temporarily (see eventual consistency below)

- Be 100% certain that one of the commits won’t fail (perhaps provided we retry it a few times)

Both of these are non-trivial, and create new failure modes which engineers have to understand and reason about.

This implementation also means that we are holding a transaction open with the main HR-World database while sending a message to our webhook service. This is considered an antipattern as the call to another service is likely to be (comparatively) slow, and we’re now making our HR-World database hold open a transaction for all of that time. Given that one of our concerns driving this project is relieving the pressure on the HR-World database, this could make our problems worse rather than better.

Another challenge is that if our webhook service is unable to accept requests, our monolith now cannot successfully create an employee; it will have to return an error as our prepare message will fail. This reduces the ‘blast radius reduction’ benefits of splitting the services as they are still too interreliant.

Eventual Consistency

Eventual consistency was the big brain idea of distributed systems architecture: what if we knew the event store would eventually catch up, even if it didn’t immediately update alongside our monolith. This is how async database replicas work, which might be used for analytics queries or periodic backups. Our webhook service is a good candidate for this. We don’t need the webhooks to be instantly created - we wait for a few events and group them together anyway, so the customer won’t notice if the event isn’t created instantly in our system provided the overall latency remains low. However, we’re still afraid of the situation where we create an employee but never send a webhook; this is something we need to avoid.

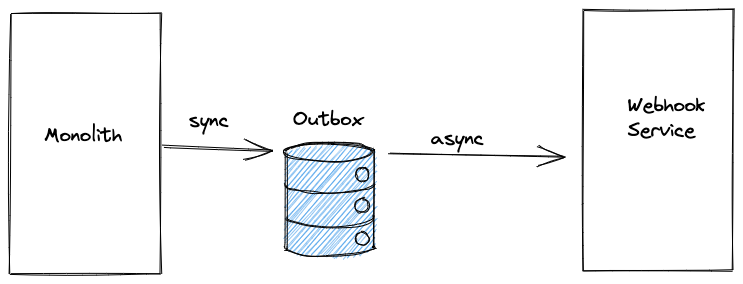

Enter the transactional outbox. For this, we need an outbox table in our monolith’s database, which can be accessed within a transaction alongside other tables in that database. This gets our ‘all or nothing’ guarantee that we expect from a transaction. We then need a process that pulls data from that table, and publishes it to our message broker. Provided this never fails, we’ve now ensured that our message will be sent without making a call outside our service.

There’s still a failure mode here. Imagine we created an employee record with a particularly long address. The employee_created event was inserted into the outbox, but when it was sent to the webhook service the service returned an error as it was unable to process this event. We either need to be able to roll back the action in the monolith (which would be surprising at best, and dangerous at worst) or to resolve whatever issue is preventing the event store from processing the message. Particularly if the product executes actions that cannot be reversed (e.g. moving money), this is something to consider carefully.

Our resolution path is likely to be either

- Alter the code in the webhook service so that it accepts longer addresses, or truncates them

- Alter the monolith code so that it truncates the address when creating the event, and edit the existing incorrect event

Option 2 should probably be setting off alarm bells: changing history like this is pretty scary and dangerous. For example, perhaps other services are also consuming these events. Do we have to go back and change them too? What happens if we now replay the events? Does something assume that events with the same idempotency key will be identical? It’s likely that you can’t do this even if you want to: at this point the message is probably in a queue somewhere which isn’t mutable. Option 1 is almost always the right solution, which means we need to be rigorous to ensure the events that are inserted into the outbox are valid.

How Long is Eventually?

One of the aims of our project is to reduce the latency on webhooks. To do this, we first need to measure the latency (using a metrics system like prometheus). We also define an SLO (service level objective) specifying that 99.9% of webhooks should be sent within 5 minutes. Once we have the metrics, we can alert (and respond) if we look to be in danger of missing our SLO. It’s useful to think in advance about what tools and options we have to manage a degradation so that when it inevitably occurs we are somewhat prepared.

Stateless Services

We can sidestep many these consistency problems if we can make a service stateless (i.e. without any persistent storage). These are sometimes described as ‘Serverless architectures’, which I consider a bit misleading but hey-ho. It’s unlikely we’ll be able to run the whole application in this way (unless it’s a fundamentally stateless product), but extracting chunks of business logic into these structures can be very worthwhile.

Looking at our requirements again:

- Storing the webhook configurations for each customer (i.e. whether they receive webhooks, and to what endpoint)

- Receiving events from the core system, grouping them into webhooks, and sending them

- Storing the webhooks that we’ve sent so that customers can view them in the UI to help debug, and resend webhooks that they failed to process

It would be possible to make a stateless webhook service but all it could do would be to deliver requirement 2: we couldn’t store the webhook configuration or record what we sent. Requirements 1 and 3 would still need to be solved by the monolith, which would now have to expose new APIs to enable the webhook service to gather configuration and store webhooks.

In the long term, it might make sense to extract either the ‘grouping events into webhooks’ or the ‘actually sending a webhook’ part of our webhook service into something stateless which we could horizontally scale. However, our current focus is on removing pressure from the primary database by breaking up the monolith, so stateless services (which by definition tend not to take pressure off the primary database) aren’t something we’d want to prioritise.

Next Up: Inter-Service Communication.