Breaking The Monolith I

Where To Start?

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a scale-up in possession of a monolith must be in want of microservices.

This series of blog posts will tell the story of a fictional startup on its journey to break the monolith. It’s informed by a combination of my experience at GoCardless, and talking and reading about similar journeys in many other startups. In this first post, we’ll outline an approach to breaking up a monolith, and then some key considerations to make the migration a success.

The Scenario

We are a high growth startup which runs an HR platform for other businesses called HR-World. It currently runs on a monolith powered by a single Postgres database, which is starting to get a bit unwieldy. We’ve got 70 engineers split into various teams working on a combination of greenfield functionality and enhancing what we already have.

Monolith or Microservices

Monoliths are awesome. Having one has allowed us to develop new product features really quickly and test them easily. Microservices might be shiny, but they are hard work and incur a lot of overhead for engineers. In simple terms, they are more complex than a monolith, and complexity = risk. As with all interesting engineering decisions, we recognise that there’s a trade-off.

The Cost of a Monolith

🏘️ If everyone owns something, no-one does. We’ve started having ownership problems, resulting in important tasks like framework upgrades becoming hard to prioritise. When something goes wrong, it takes time to work out which team needs to be informed or alerted. That has led to alert fatigue as one corner of our product isn’t very well maintained at the moment and causes lots of noise. We’re starting to see signs of ‘broken windows’ where small bugs are left to rot as no-one can agree who owns them.

💥 The blast radius of each incident in our product is becoming a problem: one team’s error can bring down the entire product, which requires everyone to be as cautious as if they owned the most business critical component. This is slowing down feature development and new joiner onboarding.

📈 Depending on data shape and storage engine, there may be scaling limits on the underlying database technology. The rate of growth in the amount of RAM required to prevent us having to do disk reads is unsustainable; we’ll soon be unable to get a big enough box. Recovery from incidents has become really slow due to data size: big databases take longer to restore, and there’s not a whole lot we can do to change that.

The Cost of Microservices

We recognise that splitting our monolith won’t magically solve all of our problems.

💬 Cross-service interfaces are hard to define, and need to be changed in backwards compatible ways, adding a lot of developer time to each interface change (e.g. 1 PR to rename a field becomes 3 PRs). This can lead to cultural pressure to avoid these changes, leaving fossilised interfaces.

🤝 Transactional guarantees across services can be computationally expensive and difficult to reason about and debug. Consistency (which is almost free in a Monolith) becomes challenging, although this is a cost of scale, not just architecture: similar challenges come from partitioning a monolith database.

🧑💻 Developer experience is likely to suffer as it’s much harder to develop, test and debug code when it is split across multiple services.

It’s all about timing

There are some red flags which have helped us decide that it’s time to start breaking apart the monolith.

- Restoring a database backup (which we test every week) now takes 5 hours, and the platform team don’t think they can optimise it further. So if we lose our database in an incident, we will have a total blackout for 5 hours while we recover the data.

- We had a severe service degradation where our whole platform slowed down because a team was running a backfill to change how we store addresses. The backfill wasn’t rate limited, which caused our synchronous database replica to fall behind, slowing down all

writerequests across the system. - There’s an increasing number of out-of-date dependencies and we rely on a handful of long-tenured individuals to keep them up-to-date, even though we’ve invested in tooling to make it easy and safe.

- Lots of support tickets are being left without an owner as they bounce between different teams, who are spending more time arguing about ownership than the time it would take to fix the ticket.

- A new team that’s starting a greenfield project about rewards isn’t delivering at the speed they’d hoped. When we investigated further, it became clear that a lot of their time was being spent putting in guardrails to ensure that their experimentation didn’t risk impacting the core product.

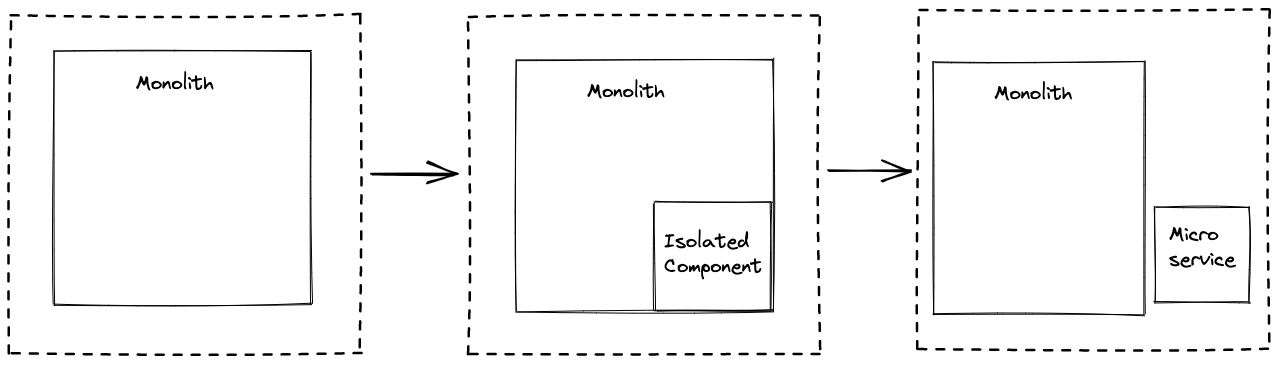

Our first service

To break a monolith, we have to start by creating our first service. Our plan is to start with a single component and complete that extraction before starting to work on multiple components in parallel across different teams. This incremental approach will help gather the learnings and build the infrastructure before we try to repeat the process many times over.

Another advantage of this approach is that it allows us to protect most of the engineering team from the inevitable teething problems of microservices, as this would both burn development time and the social capital of our ‘breaking the monolith’ project. We want to create a blueprint (with some lessons learned) which can be shared across the organisation and allow multiple teams to start extracting components.

Choosing the first component is important: there’s a Goldilocks Zone where the component is not so large and coupled that it becomes an impossible task, but not so small and isolated that we won’t learn anything from extracting it.

Also important here is the team which owns the component: ideally it should be a team that is working well together, has a reasonably limited maintenance load (so they’re unlikely to get distracted), and is interested (and ideally has some experience) in the underlying infrastructure.

We’ve decided that our first new service will manage our webhook sending code. When an employee changes their personal information in HR-World, we send a webhook (if configured) so that their employer can update it on their other systems (e.g. payroll). We also send webhooks whenever an employee joins and leaves the company, or changes role. We believe this component is in the Goldilocks Zone in terms of size and coupling. It is also at the edge of our service: there are no downstream dependencies so it’s easy to imagine how to extract it from the core system. The team that owns the integrator-facing part of our product is well established as a high-performing team, and one of the members has been helping drive the ‘breaking the monolith’ initiative within engineering.

Business Logic Changes

The team has a number of improvements they’d like to make to the webhooks, including:

- Allowing integrators to choose which webhooks they receive

- Batching the webhooks more effectively so we send fewer, bigger webhooks

- Reducing the average latency (from when the employee takes an action, to when the webhook is sent) which currently spikes when the database is under heavy load.

It is tempting to use this as an opportunity to completely rewrite our webhook sending application code and alter the business logic. This has a number of benefits:

- Coupling the technical re-architecture with more tangible and immediate business value can make the project easier to prioritise, and can act as a forcing function to push the organisation to release the new service (sometimes a service can sit in ‘shadow mode’ for weeks or even months if it’s not urgently required).

- It’s a great opportunity to reduce the complexity of the component in areas where it isn’t providing value. We currently support multiple authentication mechanisms on our webhooks, but we built that to support a particular customer who has since churned. Maybe we can remove that functionality? Perhaps we can also drop that legacy code which we haven’t used in 2 years?

- It may be required as it may be expensive or impossible to reproduce the current logic while isolating it into its own service (e.g. if the current design relies on cross-component transactions).

There are also drawbacks to this approach:

- We’ve got a long list of features we’d like to add, if we try to build all of them into this project then we’ll take multiple quarters to complete it. That will slow down gathering learnings from the microservice part as we won’t learn about that until we’re done messing with the business logic.

- The team’s focus is now split between the business logic changes and the service deployment changes, and they may not focus enough on the deployment side to gather learnings effectively

- It can be hard to evaluate the performance and correctness of the microservice if it cannot be easily compared to the existing code within the monolith

Incremental extraction can help us balance these concerns.

Incremental Extraction

Step 1: Create an isolated component inside the monolith, making any required / desired business logic changes. In our case, we’re going to focus on the webhook batching and latency as they are closely connected to the deployment mechanism, and the highest priority items. This allows the team to focus on (and test) those changes, reasoning about them in the context of ‘how can we extract this to its own service’. It’s important that we avoid implementing anything which can’t be supported across services at this stage or it’ll make the extraction much more painful. Once this is deployed, the team will have found all the interfaces and hidden dependencies / coupling in the system, which will be invaluable when extracting the service. We can take some time here to measure the performance of the system - latencies, average payload size etc. This will act as a baseline for when we extract it into its own service.

If the component is already highly isolated and decoupled with clearly defined interfaces (inside the monolith), we’ve essentially done the first step at some point in the past (yay) and can skip to step 2.

Step 2: Extract the component into its own service. This is a great example of ‘do the hard thing to make the change easy’. We’ve just loaded the entire webhook component into the proverbial RAM of the team, and given ourselves some time for ideas about how to architect the new service to mature. Everyone is now aligned with what the challenges are for this extraction, and we can focus on the most difficult problems related to the new deployment structure. We should also take this opportunity to build reusable tools to help solve common microservices challenges (e.g. inter service communication, transactional guarantees, tracing etc.). We’ll talk more about these in the next two posts - for the purposes of this story let’s assume that everything went swimmingly.

Go, Go, Go!

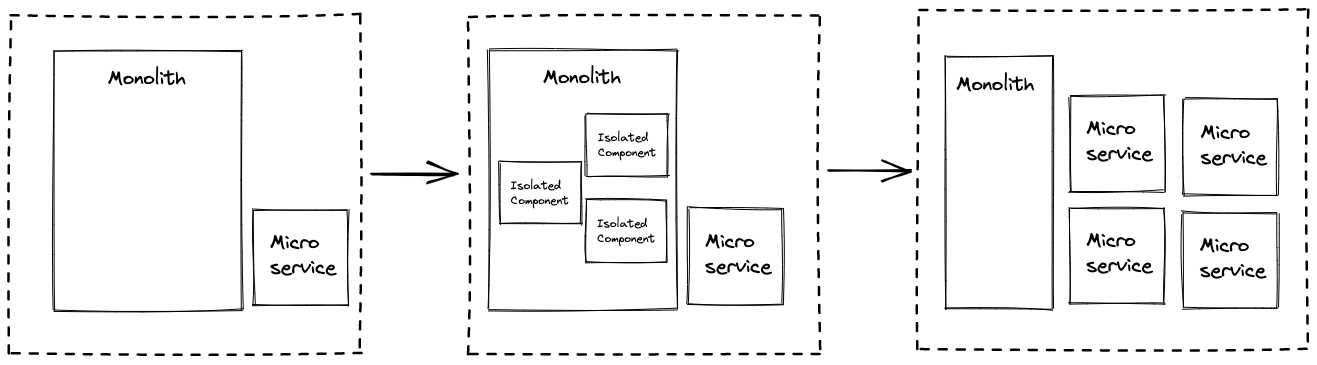

Once we have our blueprint, we can then start to parallelise our efforts by having multiple teams working on extracting different services.

Next Up: Transactional Guarantees.