Breaking The Monolith (Bonus)

Event Counting

When breaking the GoCardless monolith, we found a really interesting problem caused by our new multi-service architecture. I couldn’t find a home for it in the Breaking the Monolith series, so it’s here in a little bonus blog.

The Problem

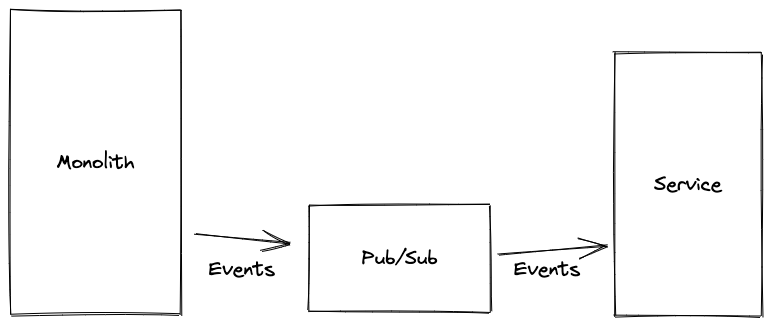

GoCardless talks to banks, and banks (specifically Direct Debit schemes) run lots of daily processes. That means that GC also has many things that happen once a day, and does lots of batch processing in what we called a pipeline. Each collection currency has its own pipeline, and each pipeline has multiple steps. For the pipelines to be successful, we needed to be sure step 1 was completed before embarking on step 2 (and so on). We kept coming up against the same problem: if the monolith emits a bunch of events, how can it be sure that they’ve all been processed by some other system before it proceeds to the next step of the pipeline.

Solution 1: SLOs

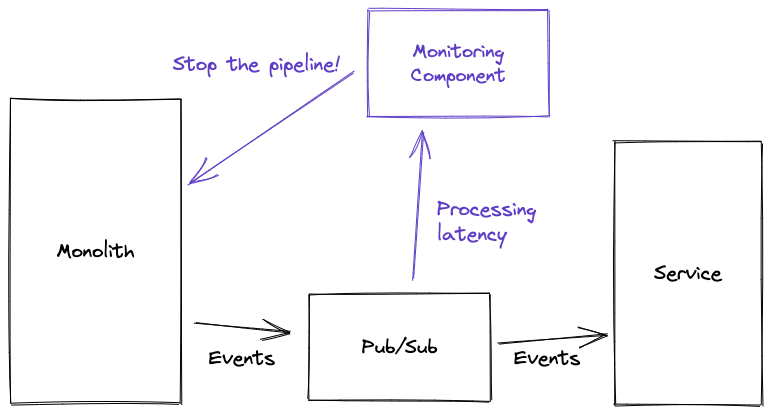

We have a Service Level Objective (SLO) set up meaning that we are alerted if a tiny % of events are not processed within the required time frame (say 5 minutes). Perhaps we can rely on this SLO, and tell our pipeline code to wait for 5 minutes after emitting the events before moving on to step 2? This means we have to really trust that our other service will meet the SLO. We also have a new and scary failure scenario, which means we have to build more tooling. If there’s a service degradation and the engineer gets alerted 4.5 mins into our 5 minute wait period, they only have 30 seconds to stop the pipeline before it moves on to step 2 (and proceeds to break). So maybe we need a new component which monitors the SLO and then stops the pipeline running if the system looks like it’s degraded. That sounds … complicated.

It also sounds a bit risky. It puts a lot of pressure on our metrics code to precisely measure this SLO, which given that we also want that code to be incredibly performant, is a bit concerning. This solution is also quite slow - we’re now waiting 5 minutes when the work will usually be completed in 1. But the real showstopper was: what happens if one of our events was in the 0.001% not covered by our SLO, so our alerts didn’t fire?

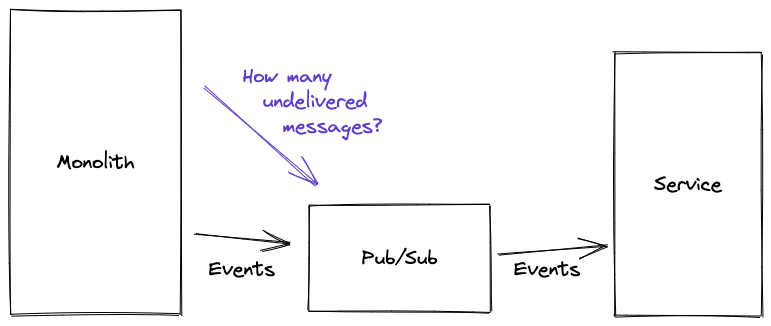

Solution 2: Look at the Queue

Another way of proving that all the events had been processed would be to look at the queue (i.e. the events waiting to be processed). If the queue is empty, then all the events must have been processed. For us, there were a couple of problems with this. Firstly, this would mean we had to have one queue for each pipeline (there are 8), and all other events would need to use a different queue. This would have expanded our number of Pub/Sub topics and subscriptions from 1 to at least 9, and again significantly increased the complexity of our system. The real problem, though, is that there wasn’t an easy way for us to query the queue - it’s not really something systems like Pub/Sub are set up to do. That tooling is all aimed at a metrics use-case, which provides different guarantees to the ones we were looking for.

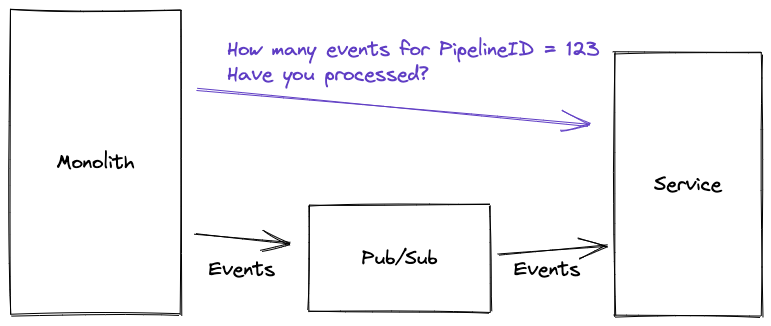

Solution 3: Event Counting

When we start a pipeline we assign it a unique ID called a PipelineID. When the pipeline emits events, it can stamp them with a PipelineID. It can also count the total number of events that it has emitted, and store this number. Our service can process the events, and also count the number of events that it has processed against a particular PipelineID. This requires a bit of thinking about transactional guarantees (we have multiple event processors which could be simultaneously updating the counter) but it’s very achievable in most databases. Our service then exposes a synchronous endpoint which returns the associated event count for a given PipelineID. This means that the monolith can poll the service to get the processed_event_count and compare it to the expected_event_count that it’s stored when emitting the events. Once these numbers are the same, the pipeline can be 100% sure that all the events have been processed, and can continue to the next step.

It’s possible (but quite fiddly) to implement this without a significant performance penalty: this kind of counting is what databases are built to do. The polling might seem clunky, but it’s incredibly cheap and pretty simple to debug when things go wrong. There’s no additional infrastructure complexity, and we’re not twisting someone else’s technology to do something it’s not intended for.

Happily ever after?

The truth is, while we’re content in a ‘engineer who solved a problem’ way with our solution, we’re not particularly happy with the overall architecture. It feels a bit like an antipattern: we’re having to force our multi-service architecture to do something unnatural. What we’d like is to be able to rely on SLOs, have genuine eventual consistency, and then have corrective actions which we can take if our services degrade. It’s OK that this isn’t perfect: in order to break the monolith, we have to be willing to make these kinds of pragmatic choices. Code doesn’t last forever, and it shouldn’t need to. If we’re too ideological, it’ll create too many cross-project dependencies and struggle to make progress breaking our monolith. So we’ve abandoned purity, and favoured pragmatism instead.