Here Be Dragons

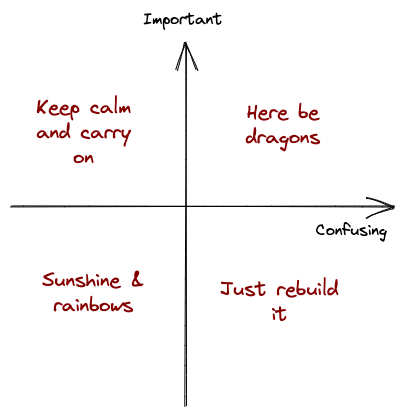

Dealing with code you don't understand

As you grow a codebase, eventually (or perhaps quite quickly) certain parts become ‘scary’. This blog post talks about why that happens, and some steps you can take to reduce the fear factor.

Why does stuff get scary?

💔 If I break it, it’s really bad

All code may be equal, but some is more equal than others. The bit of code that means we take the wrong amount of money from a customer is more scary than the bit of code which localises the API error messages. This isn’t really fixable - there’ll always be important code - but means you’ll have to think more carefully about testing and release strategies in these areas.

🤷 I don’t know what it’s actually doing

Some code is hard to read. Maybe it:

- is doing something really complicated

- was written in a rush

- is in an unfamiliar language

- is highly optimised

- has been vastly adapted from its intended use-case

- was written by someone with an unusual style

- has no documentation or tests

However it came to be, it’s now a struggle to understand what the code is doing. That makes trying to change stuff really scary (and high risk).

🤔 I don’t know why it’s doing something

Sometimes you encounter code where you don’t know why it’s there. You can see what it is achieving (that’s more the readability point above) but there’s nothing in the comments / commit history / tests / institutional memory which tells you why. This is why good commit messages are so important to maintaining a code base long term. Without understanding why, it’s hard to know which logic you need to keep versus which is no longer required or perhaps actively unhelpful.

How did we get here?

Every engineer would like to think that their code will never become scary. The evidence suggests otherwise. We often make trade-offs where we prioritise speed of delivery or speed of processing over readability. Engineering teams often have significant churn, so the likelihood of whoever wrote the code still being around is not that high. Particularly at the start of a start-up’s life, lots of code is written very quickly, usually with more fous on the here and now than the poor engineer reading it 5 years down the line. This process is also called ‘code rot’, which in my experience is an inevitable part of software.

So, What Next?

There is always the ‘Do Nothing’ approach. And it may be the right call: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. However, at some point this will no longer be the correct option. Leaving scary code unchecked causes all sorts of long-term issues: features get abandoned because ‘we can’t change the scary code’ and incidents happen when the code doesn’t behave how you expect or account for some specific situation. There are a few things that might tip you over the edge here; often it’s an incident, sometimes it’s a feature request, sometimes it’s an engineer with a personal grudge or if you’re doing really well it might have just bubbled to the top of your tech investment to-do list.

The rest of this post is a step-by-step guide of how to ‘deal’ with scary code - which is all based on the premise that you are trying to refactor a system without significantly changing it’s behaviour. Not everything will be relevant for everyone, but I hope there’ll be some useful advice all the same. I’ve used this a few times recently on features as different as API permissions and an ElasticSearch integration, with great success.

👉 Step 1: Identify The Scary Stuff

Having regular discussions about which bits of code are most ‘scary’ should be a normal part of managing your code base. Most developers make these judgements quite naturally - usually independently from one another - when estimating the complexity of a project or ticket. However, talking about it and aligning can be really productive by:

- sharing knowledge about where scary code might be hiding

- identifying who has the most context on a given scary thing

- finding the scary code that is most likely to bite you next (and prioritising fixing it)

⚙️ Step 2: Small, Safe, Incremental Refactors

This step is primarily targeting the readability problem. You probably also want to add some tests here (if the coverage is poor) to help give confidence that you aren’t changing any behaviour. They can also act as documentation for the expected behaviour of the system. The great part about this process is that you can do it incrementally in between bigger pieces of work - you’d be surprised how quickly you can increase the readability of code with some sensible variable name choices or re-organisation of classes. This will also help you understand more about the scary code, and it’s likely you will find more of the ‘I don’t know why this is here’ code. We’ll deal with that in step 3, but it’s worth adding comments as you go, for example:

# TODO: We don't know what this is doing, we suspect it's something

# to do with rounding

You may find that this process moves the code out of the scary bucket, in which case congratulations, you can go back

to building features.

Another focus here should be breaking up the scary code into smaller, more manageable chunks. If you create clearly defined interfaces between them, that allows you to tackle each section one-by-one. That means you can prioritise certain parts (e.g. the place where you need a new feature) without needing to change everything.

🔎 Step 3: Investigate

This is mostly to understand why the code is behaving in a certain way. Your first port of call here should be the code itself

(and comments), followed by a git blame to find any commit messages or PRs that might help you out. You also probably want

to ask the longest-tenure engineers if they remember anything, and also dig through any documents they might have written at

the time. Discoverability of documentation is hard, and most companies aren’t very good at it, so have a think about what will

make this easier next time round. This is often the bit which gets harder over time, particularly the ‘ask the engineer’ part,

which is one of the reasons that scary code almost always gets scarier.

👀 Step 4: Observe & Compare

Assuming all of that fails, try to isolate bits of code which don’t make sense, keeping them as small as possible. Then add a flag to disable that logic / use something different. Then write something that runs the code with your alternative logic and compares ‘what we actually did’ vs. ‘what we would have done without the unexplained logic’. You’ll want to be careful running this kind of code - ideally you’d like to run it in a test or staging environment, but id it’s got to be in production then use low priority resource and try to avoid any user impact. The comparison obviously depends on the type of change - you might be comparing some data output or performance metrics. You can then log any times where the results are ‘different’ (whatever that may mean), and then manually inspect them. This should give you a good chance to understand why that code is there. If the results are not meaningfully different for a large enough sample size (this one’s up to you), then probably change the logic in the existing code. 🤷.

For performance reasons you may want to use sampling so you don’t double-process everything, e.g. only compare 1% of requests.

If your codebase has lots of tests (that are not perfectly organised), I’d also just recommend making a change and running your whole test suite to see what breaks. That’s got me out of jail a couple of times answering the why is this here question.

🛠️ Step 5: Refactor, Rebuild or Walk Away

Once you have a clear understanding of what your code does and why, it’s lost most of its scariness. The main thing left is probably importance - or cost of failure. There’s a fork in the road here: do you want to refactor the code (i.e. return to step 2) or do you want to rebuild something new? Or have you solved / abandoned the original problem? The trade-offs there are out of scope for this post, but either way the first 4 steps should put you in a much better position to make that decision.

From here on in, the approach to this is the same as any risky change - thinking about silent releases, cutover hygiene and observability. That’s a topic for another day.